Update (Oct. 26th) : Better interpolation = better shaping, and the simpler “inscribed square” method.

Update (Nov. 4th) : Exact and customizable solution!

The input values of thumbsticks on an Xbox 360 controller are always contained inside the unit circle, a disk centered on the origin and whose radius is 1. This is usually fine, because you want to interpret the values as a vector inside that circle… but if you want to provide an analog version of a D-Pad, for instance to control a character in a 2D platformer, then you’ll find that your character will never reach maximum horizontal speed unless you hit the (1, 0) or (-1, 0) vectors, exactly right or left. Anything tilted up or down will give a fractional speed, and if you hit a diagonal corner, you’ll end up with ±√½.

So what if the analog stick was a square area instead, such that the entire circumference has a least one component maxed out, like the contour of a square?

It may seem like a simple thing to do, but it proved to be a lot of trouble, and in the end I chose to use an approximation (nope, it worked out in the end!)… but here’s how I researched the problem.

Attempt #1 : Wrong way around

I first googled “Mapping circle to square“, and ended up on a blog entry that describes the inverse transform. Fine, I’ll just invert it, isolate the x and y variables as a function of x’ and y’… But that proved to be a problem.

Wolfram|Alpha doesn’t know what to do with it, and after making it more manageable (for x, for y), it gives 4 different answers that seem to work only for specific intervals, but doesn’t say which…

I tried doing it by hand and was stuck early on, because I suck at this.

And since I don’t have access to (nor know how to use) proper nonlinear equation solvers, I decided to give up.

Attempt #2 : Projections

By googling some more and varying search terms, I stumbled upon a cool flicker image titled “Conformal Transformation: from Circle to Square“. That’s exactly what I need!

But alas, it involves something called elliptic integrals and this also goes beyond my math understanding, or the amount of effort I was willing to put in this. The description also links to the Peirce quincuncial projection, which maps a sphere to a square, but the math also goes above my head (complex numbers arithmetic and again, elliptic integrals).

At this point I realized that what I was trying to do was not trivial.

Attempt #3 : Intuition serves best

So I just went back what I usually do : analyze the problem, determine what I expect as a basic solution, and work my way there.

- Problem : The smallest horizontal component I end up with is ±√½, or ±~0.707, when the θ angle is π/4, 3π/4, 5π/4 or 7π/4.

- Solution : Scale this to ±1, so by a factor of √2.

The scale for angles close to diagonals should fall down to identity (1) when it reaches a cardinal direction, though I’m not sure about the interpolation curve… Linear should do fine?

(code removed because it’s kinda shitty)

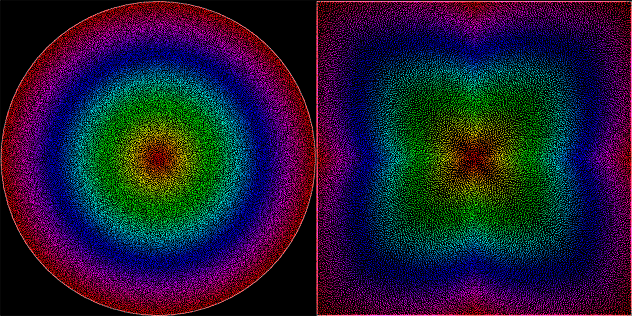

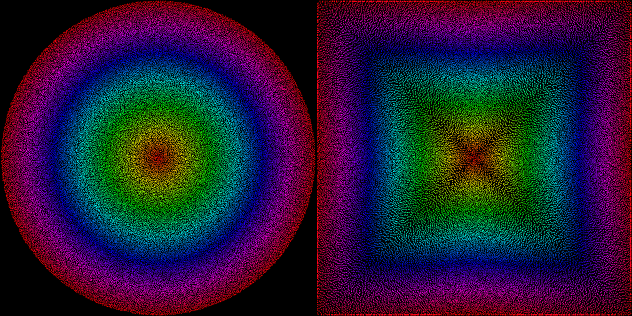

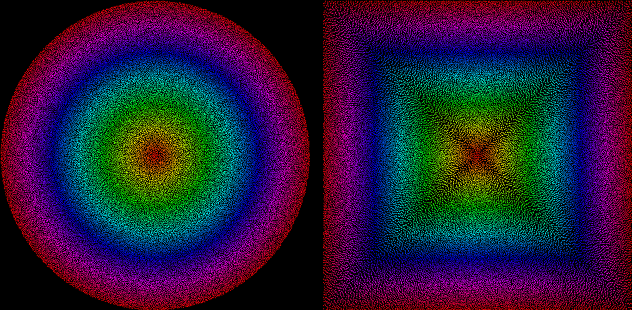

And for additional fun and testing, here’s how evenly-spaced random points inside the unit disk stretch to the unit square using this function (points generated by my Uniform Poisson-Disk code) :

Not bad? Good enough for me.

Attempt #4 : Interpolation and variations

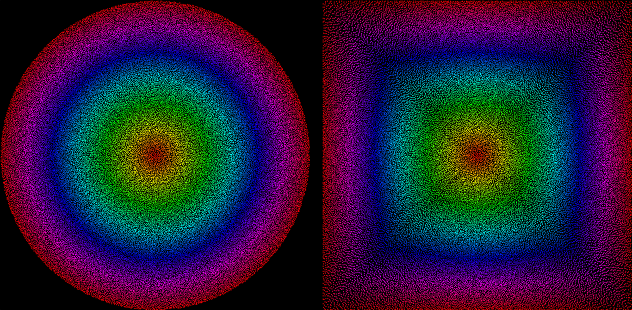

I then tried different interpolation/easing methods for the scaling factor, and tried raigan’s idea of just scaling and clamping linearly the circle to a square, here’s what it looks like!

I tried sine, quadratic and circular ease in/out/in-out from my easing functions library, and quadratic ease-in was the most balanced. It almost shapes everything to a square, very little clamping is necessary, so I’ll keep that in.

The inscribed square method is nice and simple, but cuts off a lot of values and keeps circular gradients in its area. But in the real world, for 2D platformer input, it’s probably just fine…

Attempt #5 : Epic win

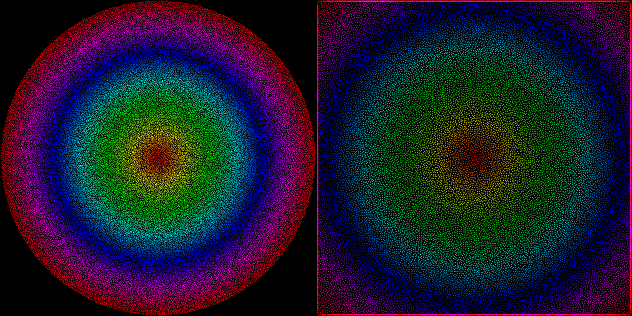

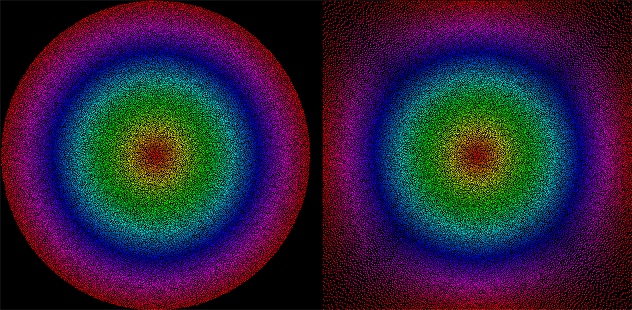

So, I decided to give another shot at this after speaking on the bus with a friend about polar coordinates and trigonometry. Turns out there is a more exact solution, and by adding a “inner roundness” parameter you can also tweak how much of the center input will remain circular, while still touching the sides for circumference values.

Here is my final C# function, then I’ll explain how it works :

static Vector2 CircleToSquare(Vector2 point)

{

return CircleToSquare(point, 0);

}

static Vector2 CircleToSquare(Vector2 point, double innerRoundness)

{

const float PiOverFour = MathHelper.Pi / 4;

// Determine the theta angle

var angle = Math.Atan2(point.Y, point.X) + MathHelper.Pi;

Vector2 squared;

// Scale according to which wall we're clamping to

// X+ wall

if (angle <= PiOverFour || angle > 7 * PiOverFour)

squared = point * (float)(1 / Math.Cos(angle));

// Y+ wall

else if (angle > PiOverFour && angle <= 3 * PiOverFour)

squared = point * (float)(1 / Math.Sin(angle));

// X- wall

else if (angle > 3 * PiOverFour && angle <= 5 * PiOverFour)

squared = point * (float)(-1 / Math.Cos(angle));

// Y- wall

else if (angle > 5 * PiOverFour && angle <= 7 * PiOverFour)

squared = point * (float)(-1 / Math.Sin(angle));

else throw new InvalidOperationException("Invalid angle...?");

// Early-out for a perfect square output

if (innerRoundness == 0)

return squared;

// Find the inner-roundness scaling factor and LERP

var length = point.Length();

var factor = (float) Math.Pow(length, innerRoundness);

return Vector2.Lerp(point, squared, factor);

}

There are two concepts here :

- The scaling factor can be calculated for every theta angle without any need for interpolation. It happens to be the inverse of the sine or cosine of the angle, depending on which wall you’re trying to clamp to. This gives a perfect square all around.

- By interpolating relatively to the length of the input vector, it’s possible to preserve the circular shape in the center and still clamp to the sides for extreme inputs.

I think I’m done with this now! Yay.